Revolutionary Memory in the Face of Capitalist Neuralyzing

Exploring the relationship of memory to capitalism and revolutionary struggle

As of now everyone has seen at least snippets of Charlie Kirk’s memorial. Most sane human beings have had the same response to that event – what the fuck was that? The internet, as usual, has done its job to spread a flurry of memes about the occasion, which resembled a WWE event more than a memorial.

We would be foolish to consider such events accidental. Capitalism shrinks from genuine memorialization. It is a system which produces an ever-present cycle of Neuralyzer flashes, readily available to try to wipe any semblance of memory.

When memories are allowed to linger it is in the form of a commodity, a real abstraction woven into the fabric of capital accumulation. It is not the memory of St. Nicholas which we keep but of Coca-Cola’s Santa Claus, a commodity we fill our homes with in December.

Likewise, irrespective of one’s thoughts on Kirk, what most substantially remains is not a real memory but a caricature, deified into a symbolic commodity whose purpose is not just accumulation, but an ideological social function used to unify people for the Zionist right’s political projects. While his persona has not died, he has neither remained alive in the form of genuine memorialization. He remains what Slavoj Žižek calls, “undead… neither alive nor dead, precisely the monstrous ‘living dead.’” He’s been turned into a zombie-like symbolic commodity for the Zionist right, an interesting appropriation considering his criticisms of Israel and AIPAC toward the end of his life.

The erasure and commodification of memory breed a memoryless people of the surface, weak and without historical depth. Like the Eloi in H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, we are conditioned to only seek immediate gratification, to shun anything that requires effort and sacrifice.

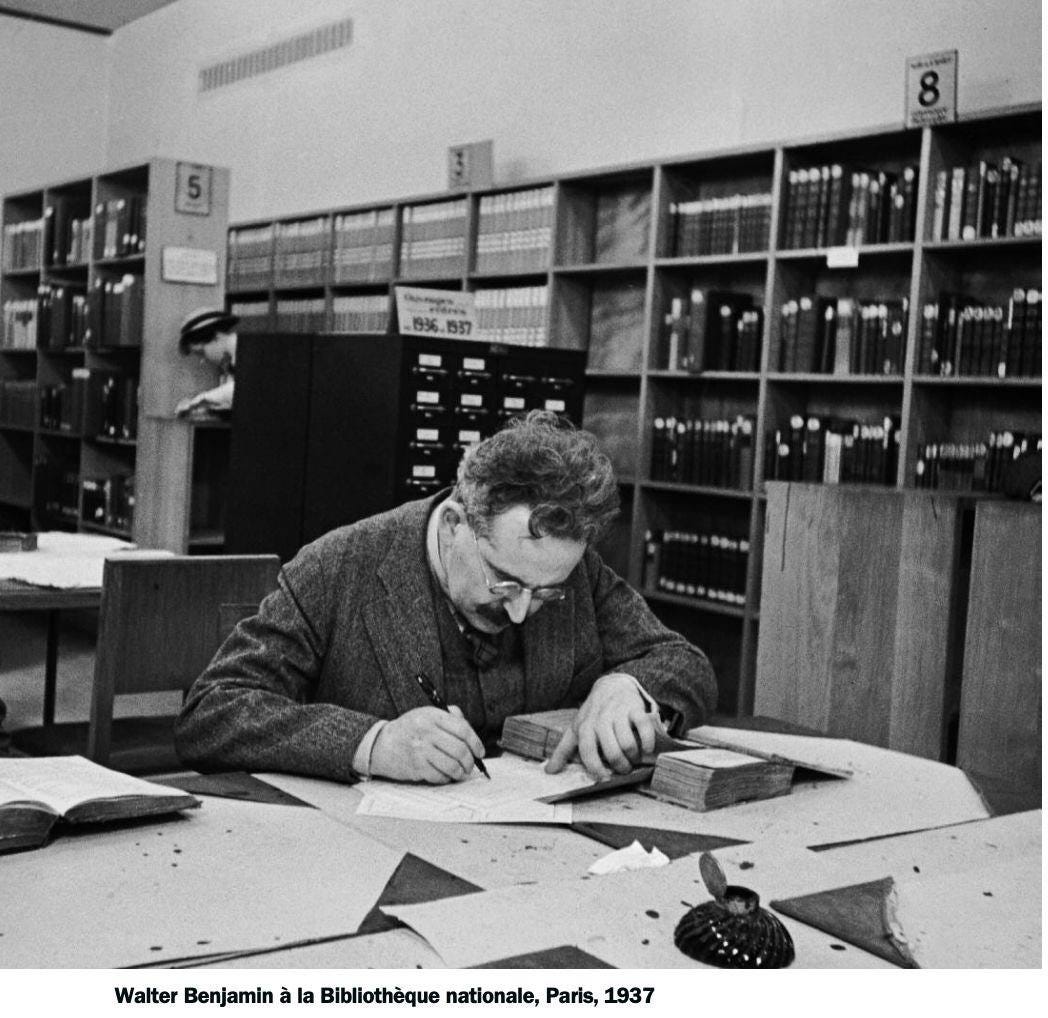

Capitalism seeks to strip us of any sense of a common historical past. It is through collective memory that a great deal of meaning is imbued to the current battles of our world – it is because our present struggles, as Walter Benjamin would say, redeem those who have fought before us that they are meaningful. It is this sense of fighting “in light” of a tradition which precedes us that sheds historical depth on our present struggles.

A people without a memory are politically paralyzed. They have the form of a people but are devoid of content. The shared identity rooted in a common tradition of struggle, its memorialization as a basic component of their being-in-the-world, is the background on which all emancipatory political projects are undertaken. This need not only take conceptual form; it is embodied in their practices, rituals, and basic ways of skillfully coping in the world.

Capitalism seeks not only to destroy how memory exists in our conceptual understanding of the world, but also in our fundamental existence in it, in the pre-conceptual practices through which we skillfully navigate the world most of the time. It seeks to uproot us from the practices, rituals, and ways of being-in-the world through which memory is sustained.

This is a fundamental mechanism of capitalism’s reproduction. It isn’t an accident or an arbitrary policy; it is a systemic necessity to continuously reproduce the system. What is at stake here is people’s willingness to sacrifice. As Boris Groys writes, humans are willing to sacrifice themselves, but there must be some semblance of compensation for it. This need not be an immediate gratification, or even one that is in our lifetime. Groys writes that “in the Christian tradition this compensation is divine grace. In our time it is the collective memory of people sacrificing themselves for the common good.”

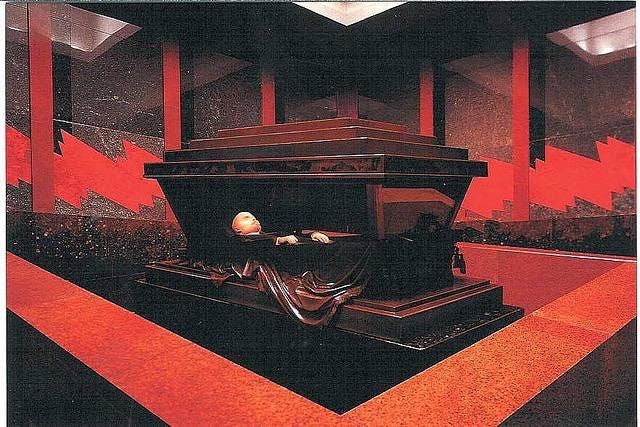

Sacrifice is often rewarded in the form of martyrdom, where the death itself becomes a testimony to the revolutionary cause. This can be seen in both Jesus and Che Guevara. Their deaths were transfigured into the collective memory of a people, their martyrdom inscribed meaning into the world from the moment of death itself. Their deaths are of the kind Chairman Mao said were “weightier than Mount Tai.” They died for the people and because of it they continued living through genuine memorialization in the people’s being-in-the-world.

Not all lives of sacrifices end in martyrdom, where the death itself is marked as a revolutionary event – a staple in the memory of the cause itself. Almost all forms of sacrifice, however, seek to be remembered, that is, to not have occurred in vain.

“It was very characteristic of the Christian church,” Groys writes, “to create an archive for sacrifice, for martyrdom. Sacrifice is always connected to the process of archiving. Capitalism tends to negate archives; today physical archives are financially in a very bad position. This economic dissolution of archives creates a feeling that whatever we do, it all disappears—it is all for nothing. If people don’t have the feeling that their sacrifice is valued, then they just enjoy life. They think the only thing they have is life here and now, so they want their life to be a life of pleasure.”

It is precisely here where we see what is at stake in capitalism’s erasure of memory and genuine memorialization. It is the uprooting of the conditions for the possibility of sacrifice – an integral quality of any revolutionary struggle. If a people are unwilling to sacrifice themselves for a cause, if they consider all sacrifices to ultimately be in vain due to the fate befallen those who have sacrificed themselves in the past, there will ultimately be no impetus to fight. Political paralysis ensues and the masses are reduced to a cattle-like existence that merely continues life to satisfy cravings and ephemeral desires.

While far from sufficient for revolutionary change, today memorialization is an essential revolutionary act. It reminds us of our forefathers who carried on the fight we wage today, in their own time. The men and women who sacrificed themselves to push things forward, even if it was not them who would reap the rewards of their struggles. Their memory must be kept alive so that their struggles don’t die in vain. So that our struggles don’t either. To remember the struggles of the past is to affirm – in the face of capitalism’s attempt to erase memory and make us into tabula rasas – that there is meaning in our sacrifices today. That our efforts will not be in vain. That however much capitalism will seek to expunge the memory of our plight from the annals of history, our descendants in the struggle will keep us alive, as we did to our forefathers. To remember is to resist a system that wants us to forget.

Carlos L. Garrido is a Cuban American philosophy professor. He is the director of the Midwestern Marx Institute and the Secretary of Education of the American Communist Party. He has authored a few books, including The Purity Fetish and the Crisis of Western Marxism (2023), Why We Need American Marxism (2024), Marxism and the Dialectical Materialist Worldview (2022), and the forthcoming On Losurdo’s Western Marxism (2025) and Hegel, Marxism, and Dialectics (2025). He has written for dozens of scholarly and popular publications around the world and runs various live broadcast shows for the Midwestern Marx Institute YouTube. You can subscribe to his Philosophy in Crisis Substack HERE. Carlos’ just made a public Instagram, which you can follow HERE.

La vida no vale nada si no es para perecer

Porque otros puedan tener lo que uno disfruta y ama

La vida no vale nada si yo me quedo sentado

Después que he visto y soñado que en todas partes me llaman

[ Life is worthless if it is not to perish

So that others may have what one enjoys and loves

Life is worthless if I sit still

After I have seen and dreamed that they call me everywhere ]

Pablo Milanés

Something I've thought about often since Kirk's assassination, is that no one has made a call-back to the 'Je Suis Charlie' trend after the Charlie Hebdo attack in 2015. To me it's an obvious connection since they were both held up as martyrs for free speech, but no one seems to have thought to get the old T shirts or hashtags out. I wonder if, because the collective psyche is so focused on the present, they have simply been forgotten